The kids got the Beatles Rock Band Limited Edition for Christmas. It came with the full regalia: the drum kit, the microphone, the Gretsch, the Rickenbacker and that great Hohner bass, and of course the songs.

This has been a pretty wonderful experience, watching my kids get steeped in the music of the greatest band in the history of the world. This is the music I grew up on, scratchy vinyl LPs of "Rubber Soul" and the "White Album" played to distraction.

Rock Band is too hard for my Vienna sausage fingers and suspect motor skills to master. It's not instrument playing, though being musical helps. The rhythmless have no chance in this game, for being able to keep a beat is essential. I mostly sit and watch, and nod pleasantly to the music.

The game is a little like Tetris with a backbeat. Notes, represented by little shining rectangles of red, orange, green, yellow and blue, hurtle down what appears to be a guitar fretboard. You press the corresponding colors on the fret of your little facsimile guitar while flipping a strum flapper, and you make music and earn points. Hit the wrong fret buttons, or strum too late, and you sound like Marty McFly at the "Under the Sea" dance, when he was about to become extinct. Mess up often enough, and it's game over.

That's fine. I'm all for building motor skills. But the real appeal is the music. It is a joyful thing, a wondrous thing, when your thirteen year old announces that "I'm Looking Through You" is about the best song he's ever heard, or you daughter perfectly masters the drum part on "Golden Slumbers/Carry That Weight/The End", the closing portion of the mini opera that is Side Two of Abbey Road, or when your older son, the one who so beautifully sang the opening tenor aria from "The Messiah" the week before Christmas, is pouring his heart and soul into mastering the screaming lead vocal on "Oh Darling". It reinforces your inner conviction that your kids are Amazing and Wonderful and blessed with that rarest of commodities, Good Taste.

We are chain makers, our actions and memories convicting us, Marley-like, or connecting us, the way Chekhov describes in "The Student of Religion". The Beatles are a few of the links on my chain, and now they are links I share with my children.

Wigilia is another one of those connecting links. This is the traditional Polish dinner, served on Christmas Eve to welcome the advent of the Lord. The menu and specific traditions vary from household to household, region to region, but there is usually mushroom soup, and lima bean soup, and fish (in our case, breaded and fried haddock), potatoes, and pierogis, little Polish dumplings filled with mushroom and potato and fried onion and farmer's cheese, boiled then pan fried in butter and onions. (For me, the meal has to include a cola beverage, too, preferably Pepsi, but Coke in a pinch, because my grandparents kept a prodigious supply of cola on hand for the holidays, wooden cases of glass bottles stacked by the steps to their tiny attached garage, delivered there by the guys who supplied Litwin's Bar and Grill down the street. Just the smell of Pepsi, and I am instantly in that tiny house on Sixth Avenue, and it is Christmas Eve and there are people crammed into every room and the dining room table takes up most of the floor space and my grandfather is playing his fiddle and singing in Polish and I'm sweaty and somehow I manage to maneuver past my siblings and my cousins and my aunt who is loud and drinks too much and her husband who is quiet and morose and Mom who always seems edgy at these things and Grandma who always looks slightly ticked off and Dad who hates every bit of the Polish food but loves Grand-pa so he keeps his mouth shut about it and sweaty and hot I get to the door in back, the one that leads to the tiny garage and it is Christmas Eve and bitterly cold and I see my breath as I stand on the stairs and I reach for one of those glass bottles and pop it open on the steel bottle opener screwed into the wall and drink and it's so cold and so good and it is almost Christmas and my grandfather is playing the fiddle and singing the Polish songs and I can hear him laughing and I feel peaceful and light.

This is Christmas Eve, a sip of cola, onions and potatoes and farmers cheese, salty simple soups and crisply battered fish. It's not fine dining. It is an aid to memory. When we take our places at the Wigilia table, eating the same things we have eaten (or pretended to eat) for generations, we are sitting with all our family. For they are all there, Mom who lives far from here, and my grandparents, who don't live at all. We are at every Christmas Eve we've ever had, every Christmas Eve we ever will have.

This year, one of my sons suggested we should mix it up a bit. Maybe next year, we could make the fish course sashimi. Sashimi is great, it's just not Wigilia. It's like playing "Spirit of the Radio" on Paul McCartney's bass: not heretical, exactly, just inappropriate.

Sometimes, things need to stay the same.

Sunday, December 27, 2009

Saturday, December 26, 2009

Boxing Day

It's a joke, OK? Today is, in much of the English-speaking world, a holiday called Boxing Day. Traditionally, it is the day that people in service industries -- the butchers, the bakers, the deliverymen -- celebrate the holiday season. It has nothing to do with fisticuffs.

I haven't written for a while. Tolstoy argued that writing, perhaps all art, burbles up out of a deep well of opposition and sadness, that when we are happy, when things are going well, the source of Art dries up. In Tolstoy's mind, the greatest works of art -- giving birth, for instance -- come only in the face of great pain and the potential for death. Christ's atoning sacrifice, that matchless art of saving souls, caused him to "suffer both body and spirit," and to ache with a depth and intensity that moves the faithful in soul-stirring ways.

Maybe I haven't been sad enough. Maybe, like the character in Neil Young's "Hawks and Doves", "I just don't got nothin' to say." That's probably not it, though. I am convinced that our Eastern European heritage includes at least some strains of Judaism. Given the places our family lived, it seems impossible for it to be any other way. The world-weary outlook of the shtetl, witty and cynical and talking a wall of words, burbles inside me. Poles, long oppressed and deeply devoted to their faith and traditions, rival Monty Python's Black Knight in their willingness to fight unwinnable battles. That's there, too. So is my father's Irish melancholy, and my mother's relentless optimism, her "The house is on fire; let's make some S'mores!" determination to see Hope in even the most dire situations. Layered over all of these often contradictory outlooks is this heaping mound of Mormonism, its own contradictions -- guilt and joy, optimism and dourness, competition and cooperation, and always, always, an abiding sense of obligation, a knowing that There Is Work To Do -- smothering everything like a cheese sauce. With all of that working, all of those emotional tectonic plates grinding grinding grinding against one another, there is always a touch of sadness, always something to say.

So maybe it's just laziness.

My audience is small, mostly indulgent family members and people who are either looking for a similarly-named wine blog, or who think "The Three Thousand Project" is a group bringing goats to impoverished Botswanan villages (Howdy, Mister Clinton!). I don't aspire to Art, either the traditional, careful-crafting-brings-transcendence kind, or the American version, Fame and A Book Deal. It's no more likely that some intrepid reader will see these words, and weeping, vow to Change His Life, than some powerhouse literary agent, having stumbled across this blog in his unending search for the next Julie Powell, sign me to a six figure advance and inform me that Meryl Streep has bought the movie rights. I do, however, have some of the actors picked out for the movie version of my life. My brother-in-law Mo will be played by Duane "The Rock" Johnson, to whom he bears a striking resemblance. My brother Nathan will be played by Matt Damon, mainly because I'm pretty sure the casting will aggravate both of them. I will be played by either Garrison Keillor, who shares both my morose mien and my rebellious eyebrows, or the angry Elf Foreman in "Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer", who has the build, the nose, and frankly, the fashion sense:

The one on the left is the cartoon elf.

This isn't Art. I write because it makes me feel happy inside. And I write because I hope that someday, my children read it, and learn something about who they are, and where they came from, and where they can turn for peace. The scary thing about writing is realizing, once the words are committed to paper or electronic media or whatever it is you're writing on, you see that it's not as good as you want it to be, that what is in your heart and your head somehow does not make the trip to your fingertips. Nephi wrote on metal plates, and he confessed that he wasn't "mighty in writing." Someone -- Fitzgerald, maybe? -- burned dozens of manuscripts, because they weren't good enough, and their flaws tortured him. In my own small and ineffectual way, I have been struggling with the same thoughts: this is no good. This does not say what I want it to say, not the way I intended it to.

But not writing is worse.

Thursday, December 3, 2009

Never Trust a Homeless Dog

A few years ago, my brother spent a summer working for me. This was before law school, before the big job in Tokyo, before he became a minor celebrity on one of those creepy Japanese comedy shows that involve people staring at one another while scorpions crawl up and down their legs and girls dressed in sexy schoolgirl costumes sing cover versions of Carpenters tunes. The Japanese have an unslakable yearning for such entertainment.

My brother and his wife lived at my office, which sounds sad, like Gob on "Arrested Development" setting up housekeeping in Bluth corporate headquarters. It wasn't like that, not much, at least. Our office is in a converted cottage, which dates to 1936. There was a kitchen and a bedroom and a living room, in addition to the rooms we use for business: it wasn't perfect, but it wasn't horrible.

Our office is in Pasadena, in a little neighborhood called "Golden Acres." It's a nice, working class area, maybe a little more bronze than golden, but nice. I really like it here.

We have homes and businesses all around us, but there are plenty of open fields very close by, and a major highway is just a block away. That means we get more than our share of stray animals. A growing family of cats lives in the stack of six inch pipes outside the fabricating plant next door. Every once in a while, I'll find a shifty-looking black cat, loitering on the front porch. I've learned not to feed these four legged hoboes; they tend to overstay their welcome when their bellies are full. I counseled Josh and Satchiko to steer clear of the vagrant hounds and kitties.

They ignored my counsel.

"We've adopted a dog for the company," he cheerily announced one Monday morning. "His name is Sticky, because we gave him a plate of pancakes with syrup on Saturday morning, and they made his snout all sticky."

These were The Days of Sticky. Every morning brought a new account of Sticky's loyalty, bravery, and intelligence. "He won't let us get too close -- I think he's afraid of humans -- but as soon as he does, we're going to bathe him and groom him and give him a real home!" Even though I'd never actually seen this animal, even though the only dogs I really care for are made by Sahlen's and come in a natural casing, I was actually warming up to the notion of a Company Hound.

Then it ended.

"Well, we finally got close to Sticky," Josh morosely reported one morning.

And did you clean him up?

"Well, when you get close to him, he's kind of scary-looking."

You told me he was a little like Benji. How could that be scary?

"He's got crazy eyes. And he growls a lot, growls and shows his teeth. And I think he has mange. He's got bugs and little white things crawling all over his fur. And he really, really stinks. I just don't think we can handle Sticky. Plus, I think he's a she, and I get the feeling there are puppies somewhere."

I finally caught a glimpse of Sticky -- who hung around for a few days after Josh stopped setting out food for him -- shortly after this conversation. The dog stood by a telephone pole, listing, like an abandoned Soviet ship, rusting in Vladivostok harbor. He (she?) did indeed have a crazy look in his (her?) eyes, and there was clear evidence of The Mange. When it was obvious that there would be no more free meals, Sticky hit the road, like The Littlest Hobo on that old Canadian teevee show, except the Littlest Hobo was clean and disease-free and he didn't hang around looking for handouts, he Solved Mysteries and Helped People In Trouble.

I've been thinking a lot about this today, mainly because our office was visited by a salesman this morning who reminded me of Sticky in a suitcoat: kind of personable and pleasant from a distance; crazy-eyed and scary up close.

So on the one hand, you could say that the lesson for today is, "Never open your door to a stray dog or a salesman."

On the other hand, I've got King Benjamin's words rattling around in my brain, reminding me that the true Christian doesn't "suffer the beggar to putteth up his petition in vain," for "are we not all beggars?"

Am I really the kind of Christian who doesn't have time for stray dogs and salesmen?

They ignored my counsel.

"We've adopted a dog for the company," he cheerily announced one Monday morning. "His name is Sticky, because we gave him a plate of pancakes with syrup on Saturday morning, and they made his snout all sticky."

These were The Days of Sticky. Every morning brought a new account of Sticky's loyalty, bravery, and intelligence. "He won't let us get too close -- I think he's afraid of humans -- but as soon as he does, we're going to bathe him and groom him and give him a real home!" Even though I'd never actually seen this animal, even though the only dogs I really care for are made by Sahlen's and come in a natural casing, I was actually warming up to the notion of a Company Hound.

Then it ended.

"Well, we finally got close to Sticky," Josh morosely reported one morning.

And did you clean him up?

"Well, when you get close to him, he's kind of scary-looking."

You told me he was a little like Benji. How could that be scary?

"He's got crazy eyes. And he growls a lot, growls and shows his teeth. And I think he has mange. He's got bugs and little white things crawling all over his fur. And he really, really stinks. I just don't think we can handle Sticky. Plus, I think he's a she, and I get the feeling there are puppies somewhere."

I finally caught a glimpse of Sticky -- who hung around for a few days after Josh stopped setting out food for him -- shortly after this conversation. The dog stood by a telephone pole, listing, like an abandoned Soviet ship, rusting in Vladivostok harbor. He (she?) did indeed have a crazy look in his (her?) eyes, and there was clear evidence of The Mange. When it was obvious that there would be no more free meals, Sticky hit the road, like The Littlest Hobo on that old Canadian teevee show, except the Littlest Hobo was clean and disease-free and he didn't hang around looking for handouts, he Solved Mysteries and Helped People In Trouble.

I've been thinking a lot about this today, mainly because our office was visited by a salesman this morning who reminded me of Sticky in a suitcoat: kind of personable and pleasant from a distance; crazy-eyed and scary up close.

So on the one hand, you could say that the lesson for today is, "Never open your door to a stray dog or a salesman."

On the other hand, I've got King Benjamin's words rattling around in my brain, reminding me that the true Christian doesn't "suffer the beggar to putteth up his petition in vain," for "are we not all beggars?"

Am I really the kind of Christian who doesn't have time for stray dogs and salesmen?

Thursday, November 26, 2009

Pre-Thanksgiving Leftovers

I want one of these shirts. Of all the Kirk McCurrays in the world, I am the Kirk McCurrayist

A few jots and tittles for ya, before you commence to consume mass quantities...

A reader asks why we've experienced Walter Siedlecki interruptus. It's a great story, and at the eleventh hour, I found some data that adds a lot of information. I want to do justice to the story, so I'm holding off. The data includes, I think, his complete military record, so that should be something worth waiting for!

The same reader wonders why the Poles did not readily assimilate into American society. It's a great question, and I will address it in a future posting. Suffice to say there are three strains of immigrants: those who came here expressly to establish a new home; those who came here as political or religious exiles; and those who came here as economic refugees. Assimilation, particularly for group two, takes generations for some groups.

I was at the bank yesterday. I've gone to the same bank for nearly twenty-four years. Our personal accounts are there. My corporate account is there. They know me. So I'm making a deposit in the drive-through lane, and the lady sends back the deposit bag with a cherry, "Have a happy Thanksgiving, Mr. McCurry."

McCurry. How I hate you, McCurry.

I tracked down another distant relative this week. Rick Heenan, of Lockport. Rick is the youngest child of Charlotte McMurray Heenan, who was my grandfather's sister. Rick is a singer-songwriter, who performs all over upstate New York. He plays something he calls "Canal Blues" -- it's good stuff!

Have a happy Thanksgiving, everybody!

Monday, November 23, 2009

Ninja

This shouldn't make me laugh, but it does.

This shouldn't make me laugh, but it does. My office is a long way from home, even by Houston standards. I face a round trip of roughly seventy miles, every single day. Each year, just in the simple, joyless task of commuting, I am driving 15,400 miles.

That's a ridiculous amount of driving. How ridiculous? Well, intrepid reader, if I were to drive from Houston to Los Angeles, and from there to San Francisco, and from there to Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver, and then take the Trans-Canada Highway through Calgary, Winnipeg, Thunder Bay, Toronto, Ottawa, Montreal, and Quebec City, afterward heading south through Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Washington, and Miami, then cut west across Florida, turn north, and take I-10 through New Orleans back to Houston, I would have driven only 8,900 miles. That leaves enough miles left over for two round trips from Houston to Buffalo. Take a minute. Look at a map. It's a ridiculous amount of driving. And all I see for all my driving is an endless string of fast food joints and the fifteen-story illuminated white cross the Southern Baptists built down near the I-45 cloverleaf. It's depressing.

So thank goodness for audio books.

I'm listening to one right now, The Men Who Stare At Goats, Jon Ronson's investigation of the US Army's forays into the paranormal. It's a bizarre and gripping story.

One of Ronson's interviewees claims that the Army had established a hierarchy of stealth skills for its paranormal forces. Level One is to subsist for a month on a diet of nuts and grains. Level Two is to master invisibility. Level Three is harnessing sufficient mind power to kill goats, simply by staring at them. These so-called "Black Operations" have been lavishly funded by the US government, which is clearly beside itself over the prospect of fielding an army of invisible vegan warriors who can kill small livestock at will.

Invisibility, Ronson's source explains, doesn't necessarily mean the ability to dematerialize. It simply means that the subject can "hide in plain sight;" that he (or she, although there is a remarkable dearth of women pursuing these things) can move in public without detection, like a boat that inexplicably leaves no wake, no ripple in the water.

I have concluded, intrepid readers, that I am close to achieving invisibility. I am on the cusp of becoming a Ninja.

Two weeks ago, one of the local news programs interviewed me, in connection to a local school board election. I wasn't running, but had been active in the campaign. Despite the reporter having written down my name, despite her having called me to double check the spelling of my name, when my large middle-aged head appeared on the 6:00 news, the graphic underneath it said, "Cort McCurry, Concerned Parent."

Yesterday, a lady at Church, a delightful, kind, friendly woman, someone who has known me for two decades, introduced me to a group of Primary children as "Brother McMurtry." And she said it three times: McMurtry, McMurtry, McMurtry.

I've written previously about the remarkable variety of sobriquets with which I've been saddled by friends and neighbors. It is a rich pageant: Kurt Corky Corey Coit Colt Curry Carey Carl Cole Horton (don't ask) Stephen (really don't ask) Peter (seriously, it's a long story) and my personal favorite, courtesy of the Los Angeles Dodgers baseball club, Kirk McGurkle. Now McCurry and McMurtry enter the panoply. People named Bob Smith don't have this problem.

What explains it? It's four lousy syllables, after all, all blessedly free of long runs of grouped consonants and disconcerting graphemes, like umlauts and tildes. I can understand honest spelling errors, adding a "u" to "Cort" or dropping the "a" from my last name, but "Kirk McGurkle"? "Mister McCurry"? "Horton"? I mean, come on!

Mr. Ronson has helped me to see the light. There's some serious mojo at work here, folks. Somehow, using powers far beyond those of mortal men, I am becoming invisible (a feat rarely accomplished by anyone wearing size 42 pants). Today, I am Coit McMurtry. Tomorrow, I am just a shadow. The day after that, it's on to Level Three.

Goats everywhere are terrified.

Saturday, November 21, 2009

Intermission

Let's grab some ridiculously overpriced popcorn and a couple of leathery hot dogs!

It's not for lack of thinking, or lack of desire. It's a lack of time.

A long time ago, when I was maybe late teens, maybe early twenties, I attended a wake for some distant relative who might have been my great-aunt. (This underscores one of the strange and distressing things about family: until my generation, no one moved very far away from the Avenues. That was Home Base, the place where your went to make sense of things. There were hundreds of us, Litwins and Siedleckis and Klimeks and others, all within a three or four mile radius of one another. The same was true on the other side of the family, even if the center point was more First Ward than Third Ward. And for all of that, I knew very few of my relatives beyond my brothers and sisters, aunts and uncles, cousins and grandparents. There was this amazing collection of second cousins and great aunts and uncles, great-grandparents even, who were like ground echoes on a weatherman's Super Doppler 3000 radar screen: they showed up, but were immediately dismissed as shadow images, nothing to bother with at all.)

This wake was held at the Saber-Skomski funeral home, on Oliver Street. There were three funeral homes on Oliver Street: Wattengel's, which serviced the folks south of Wheatfield Street, the Italians and the Irish and the intermarried Germans and the people who had been around since before the lumber mills died; Saber's, which by my time had been sold by the Saber family, and had been renamed Saber-Skomski's; and Pawenski's, which was next door to OLC Church. Saber's and Pawenski's battled for the Polish business. Pawenski eventually sold out, to a really kind man named Larango. This was an earth-shattering event in the Avenues, an Italian running a business, a business that handled OUR KINDRED DEAD, no less, operating in the shadow of the OLC spire. I remember hearing my grandfather speculate on double coffins and Secret Mafia Burials and all sorts of things worthy of a Mario Puzo novel. It wasn't like that, not at all. Mr. Larango was a professional, through and through, and his funerals were conducted with grace and class and sensitivity to the needs of the bereaved. He even kept the Pawenski name on his business for years, "Pawenski-Larango Funeral Home", a sort of vestigial Polonia. My grandmother's funeral was done by the Larangos (knowing what I know about my grandmother's early career as a bootlegger and putative moll for the infamous Dutch Schultz, she might have gotten a kick out of waiting for the Judgment Day with some Mob hit as a coffinmate, but no such luck).

I digress.

So I'm at this funeral, and I'm young, maybe late teens, maybe early twenties. And it is raucous, as raucous as such an occasion can be. There is a haze of cigarette smoke. I may be imagining it, but I swear there was an open bar. Kids were running around, adults were laughing and talking too loudly. It was a party.

Off in the corner, ignored, was the coffin, its lid propped open, its occupant a tiny, impossibly old woman, dressed in something that looked as old as she was, delicate and white and trimmed with lace. As far as the rest of us were concerned, the laughing, smoking, sweating folks who for one reason or another were tied to her, were part of her legacy, she may as well have been an umbrella rack, or one of those hedgehog things you use to scour mud from the soles of your work boots, something in the room, but not worthy of notice.

Except for one little couple, a man and a woman, as tiny and old and unnoticed as she was. They held fast to her casket, peered into it, the man's head bowed, the woman's lip moving, but barely, and whether in prayer or conversation I cannot say.

These people were related to me. And if they weren't, they surely knew my people, surely experienced the things they experienced. Maybe the old man had crossed the Atlantic on the same ship as my great-grandfather, Piotr. Maybe the women worked together on the ladies' auxiliary at OLC Church, or attended dances at Dom Polski or the Polish Falcons. Maybe they all did shift work down at "The Bolt", and ended the week with a beer that had been brewed down in the basement of Litwin's Barber Shop. And now it's all lost, all dust, all shadows and suppositions. Ghosts.

This can't happen anymore. We have extraordinary technology at our disposal. Everybody can be Ken Burns. Everybody SHOULD be Ken Burns, provided they don't all grow wispy beards and Beatle bangs and move to New Hampshire and turn every documentary into a White Guy From New Hampshire's Commentary On Black Oppression in America. I mean, sheesh, Ken, you're talented, but you live in the whitest place this side of a jar of mayonnaise. Spare us the moral outrage, already.

Anyway, I digress. Again.

My point is that everyone should be taking family histories from their parents and grandparents and aunts and uncles and kindly old neighbors and anyone who's willing to talk. We need this information. We need to remember it, to cherish it.

Another one of the many things I love about Mormonism is that its most sacred text, the Book of Mormon, is really nothing more than a family history. It's one family's story, told over dozens of generations. And the record was kept for the benefit of their children and children's children and on and on.

Why is my family's story, or any family's story, any less valuable?

So I've been busy, and honestly, a little discouraged: part of that discouragement comes in accepting the truly depressing limits of my ability. I just finished reading a book by Lawrence Weschler, Everything That Rises, and it was illuminating and brilliant and thoroughly enjoyable, and I will never write anything like it. It's like listening to The River in its entirety, or having your iPod on shuffle and hearing "For No One" for the first time in months and realizing that Paul McCartney was twenty-five or twenty-six when he wrote it and you could write until you were one hundred and six and never come close to creating anything as perfect or as beautiful. You realize that Szymborska's poetry just isn't in you, that you will never craft something as exquisite as an Olmstead park or as clever as a Dylan lyric, never accomplish the modern art genius of Dominik Hasek flailing between the pipes, arms and legs, stick and trapper flying like paint from Pollock's brush, that it is all beyond you, so why even bother?

You wallow in that a while, feeling sorry for yourself, wondering why a cruel God would make you Felix Unger at the Met, surrounded by great voices, your own a sad dissonant screech.

Then you get over it. And you start writing again.

It may be junk, intrepid readers. But like those leathery hot dogs in the theater concession stand, it's here.

Thank you, Lynda, for your encouragement.

Saturday, November 14, 2009

Walter Siedlecki and the Liberation of Poland

One of Haller's recruitment posters, circa 1918

We'll talk about Haller next time.

Nothing is new. In a nation that is built as much on the doctrine of collective amnesia as it is the concept of individual liberty, we convince ourselves that every event is fresh, our flag perennially planted in virgin soil, every crisis unique, every battle and every discovery something the world has never seen before. It isn't, not a bit of it.

Our naiveté isn't bad, not always. Sometimes, it's almost endearing, like watching a toddler working one of those wodden jigsaw puzzles, who discovers, to his surprise and delight, that if you put the pieces together in just the right way, they make a horse, or a dolphin:

Sometimes, it's creepier, more like Madonna, who appears to have based her entire career upon an unassailable conviction that she is the first person on earth to discover the genitals. And other times, like when we step over the ruins of the British Army and the Soviet Army to fight a war in Afghanistan, it's just plain stupid.

Let's send her to the Khyber Pass...she

could gyrate those pesky Taliban into submission.

All of the things we struggle with today -- economic woes, unpopular wars, caring for the needy, protecting our borders, education, advances in technology, environmental concerns, you name it -- has been faced by generations before us. We ignore lessons that could help us, lessons that could bring much needed perspective, because we are so certain that our situation is unique, our moment in history unparalleled and unimagined by who went before.

There are uncanny echos of the past in our current debate over immigration reform. Between 1880 and 1914, 2.2 million Poles immigrated to the United States, representing 2.9 percent of the nation's total population. Most estimates put the total number of Mexican immigrants currently living in the the United States, both legal and illegal, at around 11.5 million, roughly 3.8 percent of the national population. Like the Mexicans today, the Polish immigrants tended to live in ethnically homogeneous communities, work as unskilled laborers, have little formal schooling, and possess a low proficiency in English.

And they were hated. Princeton professor Woodrow Wilson, soon to become President of the United States, writes in his 1902 volume History of the American People:

... but now there came multitudes of men of lowest class from the south of Italy and men of the meaner sort out of Hungary and Poland, men out of the ranks where there was neither skill nor energy nor any initiative of quick intelligence; and they came in numbers which increased from year to year, as if the countries of the south and Europe were disburdening themselves of the more sordid and hapless elements of their population, the men whose standard of life and work were such as American workmen had never dreamed hitherto. (boldface added)

Compare these comments to those of erstwhile presidential candidate Senator Tom Tancredo, who in 2008 described Mexican immigrants as "pushing drugs, raping kids, destroying lives..." and, because of their continued use of the Spanish language, contributing to "the further Balkanization of American political life."

We were -- we Italians, we Hungarians, we Poles -- the Mexicans of one hundred years ago, derided, despised, and distrusted by mainstream America.

It was worst for the Poles. Poland had not existed as a nation for decades, partitioned in the late 18th century between Prussia, Russia, and the Austro-Hungarian empire. In the Germanic portion of the divided nation, the Polish language was outlawed, city and place names were changed from their traditional Polish to German equivalents (Gdansk, for example, became Danzig), and the practice of Catholicism was severely curtailed. By the late 19th century, the Germans had instituted programs of Kulturkampf (an effort to excise all vestiges of Polish culture from the Germanic section of the partition that included jailing Catholic clerics and closing schools that taught Polish) and Austrottungspolitk (literally, "policy of extermination," exactly the same term Henrich Himmler used in 1943 to describe the Nazi approach to the Jews). Polish families were forcibly removed from desirable properties, and replaced with German squatters. Similar practices were employed by the Russians. The Austrians did afford the Poles a measure of self-identity, with little curtailment of religious practice, although German replaced Polish as the official language, and an old term, "Galicia", replaced "Poland" as the name of the region. Buildings that had served as palaces for Polish royalty were refitted to serve as barracks for Austrian soldiers.

The Poles who arrived in America had suffered at least three generations of political and cultural oppression. They were desperately poor: the average annual salary of a worker in partitioned Poland in the 1890s was $22, or about $450 in today's currency. (By comparison, immigrants could make as much as $8 a week in American factories; much like Mexican workers today, the Poles found the economic opportunities so compelling, coming to America seemed like the only thing to do.) They had managed to retain a sense of national identity only through sheer force of will: they often worshipped in secret, spoke the language of their fathers in secret, taught their children their heritage while hiding from prying eyes of the state.

An element of siege mentality had become a part of the culture, and it carried over into their American lives: neighborhoods like the Avenues in North Tonawanda, or Hamtramck in Detroit, or the Fruit Belt in Buffalo were insular, close-knit, and almost entirely Polish. Staying together and separate was a means of self-preservation; you never knew when the policemen or the soldiers would come pounding on your door.

Couple this siege mentality with America's nativist tendencies and the disregard for immigrants expressed by even learned men like Professor Wilson, and you have the perfect conditions for a culture war. The immigrant Poles, long denied the right to express their patriotism and their religious faith in public, were given to proud displays of the national colors of red and white, and of Our Lady of Czestochowa, the icon supposedly painted by Saint Luke and revered as the Queen and Protector of the Polish people. Outsiders interpreted these displays as strange and threatening and somehow un-American, complaints strikingly similar to those leveled against Mexican immigrants today.

Rochester, New York, 1920 -- Dressed in traditional Polish costumes for the "Homelands Exposition"

Wichita Falls, Texas, 2009: Dancing in a Fiestas Patiras celebration

Poland's "Queen and Protector", and Mexico's Virgen de Guadalupe, "The Empress of the Americas"

This distrust was deepened in 1901, when a mentally disturbed Polish-American named Leon Czolgosz (who, contrary to myth, was actually born in the United States, albeit to Polish immigrant parents), shot and killed President William McKinley at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo.

Czolgosz's affliliation with anarchist groups led to speculation that the Polish community was a Fifth Column in the body politic, secretly organizing a terroristic overthrow of the American way of life. (Compare this to anti-Islamist sentiment in the weeks after September 11th. A recent Pew Research Center poll shows that roughly half -- 46 percent -- of America believed that Islam encourages violence, and has an unfavorable view of the religion. For you Mormons out there who are nodding your heads in agreement with those assessments, be warned: the same survey showed that 49 percent of those surveyed have an unfavorable view of Mormonism, and the worst thing we've ever perpetuated on the American public is Glenn Beck. Imagine what they'd think of us if some lunatic Mormon blew something up...)

Leon Czolgosz and September 11th terrorist Mohammed Atta: Crazed extremists, or the voices of their people?

A homeland bound by a century of government-sanctioned oppression. A trans-oceanic emigration, for the privilege of working at bone-grinding manual labor. Distrust and outright mistreatment in your new homeland. This was the life of the the Polish immigrant.

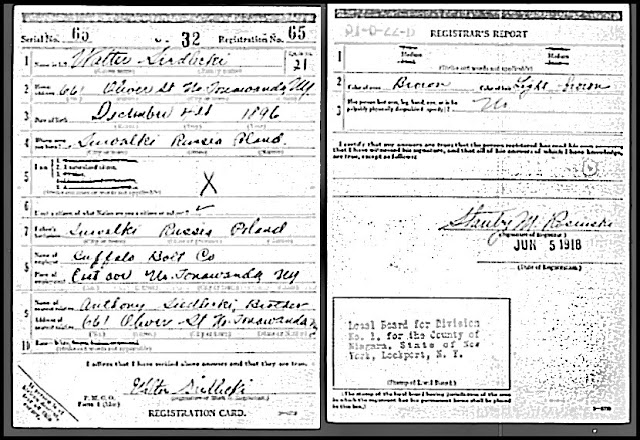

All of that makes this document remarkable:

This is Walter Siedlecki's United States draft registration card. On 5 June 1918, he presented himself to his local draft board, ready, willing, and able to take up arms in defense of the United States.

There are a few really interesting pieces of information here. First, it's noteworthy that he uses the Anglicized name Walter, not his native Waclaw, indicating if not a desire to become fully Americanized, at least a recognition of the need to appear American. Second, he lists his birthplace as "Swoalki, Russia, Poland," which is significant. "Swoalki" is probably a misspelling of Suwalki, a large, surprisingly lovely industrial town in the northeast corner of Poland, close to the Lithuanian border. This would have been in the Russian-controlled part of divided Poland, which makes his insistence that he was born in "Russia, Poland" a poignant and powerful declaration of identity, a sign that he and his family had not been willing to assimilate into the oppressor's culture. Prior to partition, Poland had briefly entered into a union with Lithuania, and Suwalki was a major point of commerce within the union. After partition, Suwalki continued to be a link between the oppressed Poles and the equally oppressed Lithuanians. The Siedleckis surely had contacts in Lithuania. He lists his employment as Buffalo Bolt, the company that employed nearly everyone in the Avenues (in another interesting contemporary parallel, my work as a Mormon bishop put me in contact with dozens of African refugees. An amazing number of them worked at the huge Goodman air conditioner plant in west Houston. If you own a Goodman, I guarantee that at least part of it was assembled by Liberian or Sierra Leonean or Nigerian workers).

Walter lists his next of kin as his brother, Anthony. Anthony Siedlecki is my grandfather. In June 1918, he would have just turned six years old. Why would Walter list a child as his next of kin? My guess is that Anthony was the only person in the household who spoke English, or who spoke it well enough to communicate with outsiders. This is consistent with the immigrant experience today: the parents may not speak English, but their school-age children do.

Walter's number did not come up; he never served in the United States military. A few months after he registered for the draft, a new opportunity arose, an opportunity to participate in the liberation of his homeland. By the early part of 1919, Walter was marching across defeated Germany, one of 23,000 American volunteers marching under the crimson and white banner of the Polish republic, marching to unify a partitioned nation.

Sorry to go all Paul Harvey on you, but next time, I'll give you The Rest of the Story....and I'll say nary a word about Bose radios or "ocular nutrition tablets" or the soft, cool comfort of Jerzees cotton tee-shirts.................Good Day!

Tuesday, November 10, 2009

Honor Roll

This is, to the best of my knowledge, a list of family members who served in the Armed Forces:

Revolutionary War (fighting for the British)

Jacob Anguish

Henry Anguish

War of 1812 (fighting for the United States)

Abram Milliman

Civil War (fighting for the Union)

Philander Eugene Pearce

British Occupation of India

Hugh McMurray

Crimean War, British Occupation of Australia, Fenian War (as a member of the Royal Canadian Rifles)

James McMurray

British Army, late Victorian period

James Ocean McMurray

World War I, War of Polish Independence (1919-1920)

Walter Siedlecki

World War II

Melvin Zuch, Pacific Theater

Ray Litwin, US Army Air Corps, European Theater

Korean War

Alfred McMurray, US Army Reserves

Some of these men fought for causes that were noble; some of them fought for imperialist powers. Some of them were brave; some were cowards. Some of them were dedicated men, trusted by their superiors and loved by their compatriots. Some of them hated military life, and served poorly. One was involved in the bloodiest 20 minutes in American history, an event of spectacular waste and destruction that haunted its architect all the days of his life. Another marched in one of the great military victories of the 20th century, a victory that his countrymen still celebrate nearly a century later. More than a few required their families to trek across oceans and wilderness, following them in their service. They wore buckskin dyed the color of a summertime forest and red coats with white breeches and blue kepis and bullfrog green tunics and olive drab and khaki, and one wore a uniform the color of the midday sky, a uniform hardly anyone remembers anymore.

They were soldiers.

Remember them today.

Revolutionary War (fighting for the British)

Jacob Anguish

Henry Anguish

War of 1812 (fighting for the United States)

Abram Milliman

Civil War (fighting for the Union)

Philander Eugene Pearce

British Occupation of India

Hugh McMurray

Crimean War, British Occupation of Australia, Fenian War (as a member of the Royal Canadian Rifles)

James McMurray

British Army, late Victorian period

James Ocean McMurray

World War I, War of Polish Independence (1919-1920)

Walter Siedlecki

World War II

Melvin Zuch, Pacific Theater

Ray Litwin, US Army Air Corps, European Theater

Korean War

Alfred McMurray, US Army Reserves

Some of these men fought for causes that were noble; some of them fought for imperialist powers. Some of them were brave; some were cowards. Some of them were dedicated men, trusted by their superiors and loved by their compatriots. Some of them hated military life, and served poorly. One was involved in the bloodiest 20 minutes in American history, an event of spectacular waste and destruction that haunted its architect all the days of his life. Another marched in one of the great military victories of the 20th century, a victory that his countrymen still celebrate nearly a century later. More than a few required their families to trek across oceans and wilderness, following them in their service. They wore buckskin dyed the color of a summertime forest and red coats with white breeches and blue kepis and bullfrog green tunics and olive drab and khaki, and one wore a uniform the color of the midday sky, a uniform hardly anyone remembers anymore.

They were soldiers.

Remember them today.

Yer Blues

It's "Guess the artist who wrote the song that shares its title with today's post" time. The answer is The Beatles, of course, "Yer Blues" being a John Lennon-penned track from the seminal White Album. Any who deign to argue that the Beatles are not the most influential and important rock band of all time are, frankly, nuts. Arguing that The Beatles are no more than a footnote in world history is a little like dismissing the Sun as a minor star: that may be true, but if it didn't exist, than neither would you, so keep quiet about it. I do not suggest that had those four lads not shaken the world, the entire planet would have collapsed on itself, in some fallen souffle-like horror of cold and darkness. What I mean is that the whole of what we call contemporary culture -- music, fashion, design, thought, all of it, for good and ill -- has its genesis in the seven year Big Bang of creativity that was the Beatles, 1964 - 1970. We would be here, but we would not be us. We would be some different people.

Maybe I overstate a bit. But I doubt it.

I am, after yesterday, at what I am calling the official halfway point of my sojourn on Planet Excitement. I plan on living until the age of 94. The remainder breaks down like this: twenty more years of work, including seeing all of our children through graduate school; twenty years of travel, gardening, and enjoying our grandkids; five years spent on some bizarre hobby that I inexplicably acquire in retirement, like collecting license plates, or obsessively watching The Weather Channel; two years of Dreamland, where past and present are all mixed together and I think that my retirement home is actually a rather disappointing cruise ship. Then it's "thanks for playing!" At my funeral, I want an all-trombone honor ensemble to play "Born To Run" as my coffin is lowered into the south Texas clay.

Well, that's kind of depressing. I had a nice birthday, except for a truly awful, stomach churning white light sear of a migraine. I haven't had one in months, and this one was a neck snapper. It's made me a little muted today. (I am better, though, something I attribute to the remarkable Blushing Peach Pie my wife made for my birthday).

There is a reason for the title, beyond my feeling a little melancholy at turning FORTY-SEVEN. Blue is a color associated with a remarkable band of brothers, men who defended their homeland from the invasion of a bloodthirsty army, in the face of open hostility from the rest of the world. And one of our ancestors was one of those defenders.

Later this week, Walter Siedlecki's military adventure.

Maybe I overstate a bit. But I doubt it.

I am, after yesterday, at what I am calling the official halfway point of my sojourn on Planet Excitement. I plan on living until the age of 94. The remainder breaks down like this: twenty more years of work, including seeing all of our children through graduate school; twenty years of travel, gardening, and enjoying our grandkids; five years spent on some bizarre hobby that I inexplicably acquire in retirement, like collecting license plates, or obsessively watching The Weather Channel; two years of Dreamland, where past and present are all mixed together and I think that my retirement home is actually a rather disappointing cruise ship. Then it's "thanks for playing!" At my funeral, I want an all-trombone honor ensemble to play "Born To Run" as my coffin is lowered into the south Texas clay.

Well, that's kind of depressing. I had a nice birthday, except for a truly awful, stomach churning white light sear of a migraine. I haven't had one in months, and this one was a neck snapper. It's made me a little muted today. (I am better, though, something I attribute to the remarkable Blushing Peach Pie my wife made for my birthday).

There is a reason for the title, beyond my feeling a little melancholy at turning FORTY-SEVEN. Blue is a color associated with a remarkable band of brothers, men who defended their homeland from the invasion of a bloodthirsty army, in the face of open hostility from the rest of the world. And one of our ancestors was one of those defenders.

Later this week, Walter Siedlecki's military adventure.

Saturday, November 7, 2009

Words, Words, Words

Shoot me, but I liked Mel Gibson as Hamlet.

Olivier's Hamlet was creepy and fey, like the Monty Python character

whose father wanted him to marry the girl with huge tracts of land...

Today is Saturday.

In the last seven weeks, I've posted roughly 32,000 words to the blog, which works out to, with illustrations, about 150 pages of manuscript. That's a lot of words.

Today, I'm going to work on actually organizing some of the names I've compiled.

Next week, pictures! And a tribute to veterans (some of which may surprise you!)

I don't know if anyone is reading this. That's really not the point. There is a little bit of Hamlet's mission in this, the ghost standing at the parapets, pleading with the living, "Remember me!" Eugene Pearce deserves to have his story known. Peter Litwin deserves to have his story known (I'm working on a song lyric for Peter, "The King of Oliver Street"). The Interweb is a better place with my grandmother's wedding photo on it. These are my people, our people (for I cannot imagine that anyone who is reading this on a regular basis is not related to me -- it's sort of like having your nut uncle run for city alderman: the only votes he gets are from concerned family members who don't want to see the old gasbag get shut out; folks who honestly thought that he was the other guy; and fellow nuts and gasbags) and these "voices from the dust" are the voices that gave us our voice.

And so, Adieu, Adieu!

Friday, November 6, 2009

The Mystery of Crooked Sally

Tyringham, Massachusetts: Heaven for painters and poets.

For farmers, not so much.

Western Massachusetts has never been a terribly practical place to live. Rocky soil, bad weather, and isolation from large population centers make it inhospitable for farming, and in the days before ours, when "sustainable and local" weren't advertising hooks, but necessities of life, bad farmland could mean starvation.

In the century following the establishment of Plimouth Plantation, Berkshire County drew many young families, attracted by the prospect of seemingly limitless land. Few of them lasted for more than a generation, their hopes dashed by the rocks and the cold and the promise of better times in New York or the vast Western Reserve. Towns and villages, many predating the Declaration of Independence, are sprinkled across the Berkshires, tiny and ancient, like so many municipal bonsai trees. Housatonic and Lenox and Adams and Stockbridge: lovely, but arrested, clipped and miniature. Few of these places are much bigger than when they were incorporated, two centuries ago.

The Berkshires have always been more hospitable for artists than farmers. Nathaniel Hawthorne lived here, and Herman Melville. Edith Wharton's estate, The Mount, is one of the main tourist attractions in Lenox. Pittsfield, the closest thing to a metropolis in the region, is home to an ancient baseball stadium, Waconah Park, and claims to be the true home of the national pastime, dismissing the folks in Cooperstown as upstarts and usurpers. Summer in the Berkshires means vacationing accountants and middle aged college professors dressed in old timey uniforms, playing Base-Ball, by the 1858 Massachusetts rules. It also means Volvo loads of Bostonians trekking out to Tanglewood, the summer home of the Boston Symphony, to eat picnic suppers and listen to the lovely music. It's a Norman Rockwell Museum, weekend antiquing trip kind of place, and has been for decades.

When Lawrence Southcotte Pearce moved his family from East Greenwich, Rhode Island to Tyringham, Massachusetts, he wasn't searching for his muse. He was undoubtedly drawn by the twin prospects of ready farmland and a measure of separation from the booming population of post-Revoluntionary War coastal towns. I have not pinned down a precise date for the move, but based on his children's birth records, it happened after 1786.

Pearce and his wife Leticia Austin had at least six children: Langworthy; John; Mary; Elizabeth; Isaac; and Sarah. Since most legal records, including census lists, didn't start listing women by name until the middle of the nineteenth century, and since women's surnames generally change after marriage, it's a lot easier to track the Pearce family diaspora through the men. The records are generally sketchy, but this is what they show:

-- Lawrence left Tyringham sometime after 1810. He died in the Town of Livingston, New York, on 12 August 1832, at the age of 87.

--Langworthy married a woman named Sabrina in 1787. They had ten children together, and both died, apparently of disease, in Niagara, New York, in 1831.

-- John M. Pearce married Sarah Sweet in Rhode Island, about 1793. Thus far, I find no record of their children. John died in Kalamazoo County, Michigan, in 1858.

--Isaac appears to have married Thankful Steadman in Berkshire County, sometime around 1804, then moved to Bennington, Wyoming County, New York, where he died in 1868. He and Thankful had at least eight children.

Were poor soil and bad weather the only factors driving all of these people away from Berkshire County? Does the story of Sally Pearce offer insight?

Sarah "Sally" Pearce was the youngest of Lawrence and Leticia's children. She was born in 1786, when her mother was forty-one years old. In 1805, at age nineteen, she delivered her first son, Benjamin Stanton Pearce. The Tyringham birth records list Sarah Pearce as Benjamin's mother; his father is listed as "unknown." The Pearce's Tyringham is only a few generations removed from Puritan times; the Puritan experience was fresh in Hawthorne's mind in 1850, when, while living in the Berkshires, he penned The Scarlet Letter. Did shame over Sarah's out of wedlock pregnancy prompt the family's move?

Who was Sarah "Sally" Pearce? Benjamin was not her only bastard son. She gave birth to another out of wedlock child, Parvis C. Pearce, on 23 May 1817, in Geneseo, New York. Another fatherless son, William, had been born earlier, in Rhode Island. His death certificate, issued in Climax Township, Kalamazoo County, Michigan, indicates he died on 7 August 1875, aged 82 years, 29 days. This puts his birthdate at 9 July, 1793. If this is accurate, his mother would have been seven at his birth, clearly an impossibility. The record also indicates that William was mentally handicapped, an "idiot since birth."

Autobiographical sketches of Parvis and Benjamin only raise more questions. Benjamin achieved some measure of success in farming, owning a large portion of land in Wheatfield, New York. He appears to have had nothing to do with his mother after about 1815, and for a time appears to have lived with another family who left western Massachusetts, the Millimans. His wife, Vashti, was the daughter of Abriam Milliman and the granddaughter of Abram Milliman, the men who seem to have been Benjamin's benefactors.

According to his biographer, Parvis and his mother moved from Geneseo to Niagara in 1830, where twelve years later he married Eliza Kelly. Looking for "rich and cheap" farm land, he moved to Climax, Michigan, and after some years of struggle (and ten children) he managed to acquire more than three hundred acres in farmland:

That doesn't answer my question: who was Sarah "Sally" Pearce?

She was a known figure in the little town of Tyringham. Records of the time refer to her as "Crooked Sally", owing to some sort of physical deformity. She was a single mother in an age a century and a half before that phrase was coined. She appears to have borne some sort of handicap, in an age where terms like "lunatic" and "idiot" were part of official parlance. The fact that her nickname is recorded on town records indicates that she was known to town officials. Did she have run-ins with the law? Where were her parents? Was she rebellious, or did they abandon her? Were her sons' fathers her lovers, her clients, or her abusers?

Sarah Sally Pearce is my great-great-great grandmother. I am here because of what happened to her, in that sleepy little town in Berkshires. Did she hate what had happened, despise the town and resent the baby? Or was she not aware enough to even understand what was happening?

I have constructed a reality for her, isolated, alone, victimized. I've even written a song lyric about her, which I may post someday. Is any of it anything close to reality, or is it all just dinosaur skin, acceptable because it's plausible?

One of the truly beautiful promises of Mormon theology is that one day, we will know things "as they really are." In that Great and Final Day, when the lines of folks wanting to talk to Lincoln and Caesar and Amelia Earhart are stretching as far as the eye can see, I'll be searching for Sarah "Sally" Pearce, learning her story.

Thursday, November 5, 2009

Stall Tactics

Admit it. You feel a little embarrassed for this guy.

I don't really want to write this entry.

It's not the subject matter, which examines what seems to be a particularly sad and shameful chapter of my family's history. Sometimes you have to talk about difficult things. You don't relish it, but you do it.

Some people get their kicks focusing on sad and shameful. I knew a guy in Buffalo who gleefully told anyone who cared to listen that one of his ancestors was hanged as a horse thief. That's like the weird Australian compulsion to remind the world that their nation started as a giant penal colony. We get it: Great Grandad was a deviant. Mazel tov, you wacko. Mike Leach, the Texas Tech football coach, is obsessed with pirates, not the ones who play baseball in southwestern Pennsylvania, but the yo, ho-ho, and a bottle of rum types, to the joyful approbation of the Tech faithful. This, too, strikes me as crazy: Pirates were psychotic, bloodthirsty terrorists, who raped and pillaged and tortured and murdered and terrified most of the civilized world (again, I'm talking about the yo, ho-ho types; the Pittsburgh Pirates don't terrify anyone, least of all the other teams in the National League). If Coach Leach chose to find inspiration in someone with similar proclivities -- Idi Amin, say, or The Son of Sam -- I doubt the folks up in Lubbock would be so sanguine. This is football in Texas, though, so he could probably prowl the sidelines dressed as Henirich Himmler and people would be OK with it, so long as he was winning ballgames. A guest on "The Dan Patrick Show" once observed that if Jeffrey Dahmer could run a 4.0 40 yard dash, football scouts would dismiss his cannibalism as "an eating disorder," so anything's possible.

It's not the potential for embarrassment that the story carries, either. I am pretty easily embarrassed, although being easily embarrassed tends to be a trait that fades with the years. I have one of those fairly high-pitched voices, the kind that mothers tell their sons is "a ringing tenor" but their best friends assure them is "really femmy sounding." My job involves a lot of telephone contact with customers. Combine a "ringing tenor voice" with a gender ambiguous name, and you are guaranteed to have old men calling you "Sweetie" and flirting with you at least a couple of times a year. When I was in my Twenties, it mortified me. Now, I just call them "darlin'" and flirt right back, unconcerned about the randy thoughts pinballing around their decrepit old man brains. I will never get used to the rampant Oprahfication of our society, where every personal matter, bedroom secrets, bathroom details, and everything in between, becomes a matter for the public record, but when you get right down to it, there isn't one of us whose presence here is not directly linked to a pair of elevated heart rates and a certain measure of stickiness, so we need to get over ourselves.

What's bothering me is that I'm not sure I know the real story of the person I'm writing about. I have some clues, but they're just bones and fossils, scraps and implications. I've sculpted a heaping load of Plasticine around these fragments, to make them into something believable.

I'm not sure I've created the right dinosaur.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)