One of Haller's recruitment posters, circa 1918

We'll talk about Haller next time.

Nothing is new. In a nation that is built as much on the doctrine of collective amnesia as it is the concept of individual liberty, we convince ourselves that every event is fresh, our flag perennially planted in virgin soil, every crisis unique, every battle and every discovery something the world has never seen before. It isn't, not a bit of it.

Our naiveté isn't bad, not always. Sometimes, it's almost endearing, like watching a toddler working one of those wodden jigsaw puzzles, who discovers, to his surprise and delight, that if you put the pieces together in just the right way, they make a horse, or a dolphin:

Sometimes, it's creepier, more like Madonna, who appears to have based her entire career upon an unassailable conviction that she is the first person on earth to discover the genitals. And other times, like when we step over the ruins of the British Army and the Soviet Army to fight a war in Afghanistan, it's just plain stupid.

Let's send her to the Khyber Pass...she

could gyrate those pesky Taliban into submission.

All of the things we struggle with today -- economic woes, unpopular wars, caring for the needy, protecting our borders, education, advances in technology, environmental concerns, you name it -- has been faced by generations before us. We ignore lessons that could help us, lessons that could bring much needed perspective, because we are so certain that our situation is unique, our moment in history unparalleled and unimagined by who went before.

There are uncanny echos of the past in our current debate over immigration reform. Between 1880 and 1914, 2.2 million Poles immigrated to the United States, representing 2.9 percent of the nation's total population. Most estimates put the total number of Mexican immigrants currently living in the the United States, both legal and illegal, at around 11.5 million, roughly 3.8 percent of the national population. Like the Mexicans today, the Polish immigrants tended to live in ethnically homogeneous communities, work as unskilled laborers, have little formal schooling, and possess a low proficiency in English.

And they were hated. Princeton professor Woodrow Wilson, soon to become President of the United States, writes in his 1902 volume History of the American People:

... but now there came multitudes of men of lowest class from the south of Italy and men of the meaner sort out of Hungary and Poland, men out of the ranks where there was neither skill nor energy nor any initiative of quick intelligence; and they came in numbers which increased from year to year, as if the countries of the south and Europe were disburdening themselves of the more sordid and hapless elements of their population, the men whose standard of life and work were such as American workmen had never dreamed hitherto. (boldface added)

Compare these comments to those of erstwhile presidential candidate Senator Tom Tancredo, who in 2008 described Mexican immigrants as "pushing drugs, raping kids, destroying lives..." and, because of their continued use of the Spanish language, contributing to "the further Balkanization of American political life."

We were -- we Italians, we Hungarians, we Poles -- the Mexicans of one hundred years ago, derided, despised, and distrusted by mainstream America.

It was worst for the Poles. Poland had not existed as a nation for decades, partitioned in the late 18th century between Prussia, Russia, and the Austro-Hungarian empire. In the Germanic portion of the divided nation, the Polish language was outlawed, city and place names were changed from their traditional Polish to German equivalents (Gdansk, for example, became Danzig), and the practice of Catholicism was severely curtailed. By the late 19th century, the Germans had instituted programs of Kulturkampf (an effort to excise all vestiges of Polish culture from the Germanic section of the partition that included jailing Catholic clerics and closing schools that taught Polish) and Austrottungspolitk (literally, "policy of extermination," exactly the same term Henrich Himmler used in 1943 to describe the Nazi approach to the Jews). Polish families were forcibly removed from desirable properties, and replaced with German squatters. Similar practices were employed by the Russians. The Austrians did afford the Poles a measure of self-identity, with little curtailment of religious practice, although German replaced Polish as the official language, and an old term, "Galicia", replaced "Poland" as the name of the region. Buildings that had served as palaces for Polish royalty were refitted to serve as barracks for Austrian soldiers.

The Poles who arrived in America had suffered at least three generations of political and cultural oppression. They were desperately poor: the average annual salary of a worker in partitioned Poland in the 1890s was $22, or about $450 in today's currency. (By comparison, immigrants could make as much as $8 a week in American factories; much like Mexican workers today, the Poles found the economic opportunities so compelling, coming to America seemed like the only thing to do.) They had managed to retain a sense of national identity only through sheer force of will: they often worshipped in secret, spoke the language of their fathers in secret, taught their children their heritage while hiding from prying eyes of the state.

An element of siege mentality had become a part of the culture, and it carried over into their American lives: neighborhoods like the Avenues in North Tonawanda, or Hamtramck in Detroit, or the Fruit Belt in Buffalo were insular, close-knit, and almost entirely Polish. Staying together and separate was a means of self-preservation; you never knew when the policemen or the soldiers would come pounding on your door.

Couple this siege mentality with America's nativist tendencies and the disregard for immigrants expressed by even learned men like Professor Wilson, and you have the perfect conditions for a culture war. The immigrant Poles, long denied the right to express their patriotism and their religious faith in public, were given to proud displays of the national colors of red and white, and of Our Lady of Czestochowa, the icon supposedly painted by Saint Luke and revered as the Queen and Protector of the Polish people. Outsiders interpreted these displays as strange and threatening and somehow un-American, complaints strikingly similar to those leveled against Mexican immigrants today.

Rochester, New York, 1920 -- Dressed in traditional Polish costumes for the "Homelands Exposition"

Wichita Falls, Texas, 2009: Dancing in a Fiestas Patiras celebration

Poland's "Queen and Protector", and Mexico's Virgen de Guadalupe, "The Empress of the Americas"

This distrust was deepened in 1901, when a mentally disturbed Polish-American named Leon Czolgosz (who, contrary to myth, was actually born in the United States, albeit to Polish immigrant parents), shot and killed President William McKinley at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo.

Czolgosz's affliliation with anarchist groups led to speculation that the Polish community was a Fifth Column in the body politic, secretly organizing a terroristic overthrow of the American way of life. (Compare this to anti-Islamist sentiment in the weeks after September 11th. A recent Pew Research Center poll shows that roughly half -- 46 percent -- of America believed that Islam encourages violence, and has an unfavorable view of the religion. For you Mormons out there who are nodding your heads in agreement with those assessments, be warned: the same survey showed that 49 percent of those surveyed have an unfavorable view of Mormonism, and the worst thing we've ever perpetuated on the American public is Glenn Beck. Imagine what they'd think of us if some lunatic Mormon blew something up...)

Leon Czolgosz and September 11th terrorist Mohammed Atta: Crazed extremists, or the voices of their people?

A homeland bound by a century of government-sanctioned oppression. A trans-oceanic emigration, for the privilege of working at bone-grinding manual labor. Distrust and outright mistreatment in your new homeland. This was the life of the the Polish immigrant.

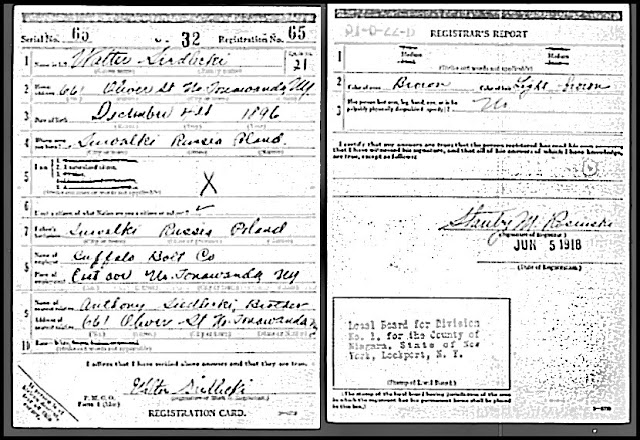

All of that makes this document remarkable:

This is Walter Siedlecki's United States draft registration card. On 5 June 1918, he presented himself to his local draft board, ready, willing, and able to take up arms in defense of the United States.

There are a few really interesting pieces of information here. First, it's noteworthy that he uses the Anglicized name Walter, not his native Waclaw, indicating if not a desire to become fully Americanized, at least a recognition of the need to appear American. Second, he lists his birthplace as "Swoalki, Russia, Poland," which is significant. "Swoalki" is probably a misspelling of Suwalki, a large, surprisingly lovely industrial town in the northeast corner of Poland, close to the Lithuanian border. This would have been in the Russian-controlled part of divided Poland, which makes his insistence that he was born in "Russia, Poland" a poignant and powerful declaration of identity, a sign that he and his family had not been willing to assimilate into the oppressor's culture. Prior to partition, Poland had briefly entered into a union with Lithuania, and Suwalki was a major point of commerce within the union. After partition, Suwalki continued to be a link between the oppressed Poles and the equally oppressed Lithuanians. The Siedleckis surely had contacts in Lithuania. He lists his employment as Buffalo Bolt, the company that employed nearly everyone in the Avenues (in another interesting contemporary parallel, my work as a Mormon bishop put me in contact with dozens of African refugees. An amazing number of them worked at the huge Goodman air conditioner plant in west Houston. If you own a Goodman, I guarantee that at least part of it was assembled by Liberian or Sierra Leonean or Nigerian workers).

Walter lists his next of kin as his brother, Anthony. Anthony Siedlecki is my grandfather. In June 1918, he would have just turned six years old. Why would Walter list a child as his next of kin? My guess is that Anthony was the only person in the household who spoke English, or who spoke it well enough to communicate with outsiders. This is consistent with the immigrant experience today: the parents may not speak English, but their school-age children do.

Walter's number did not come up; he never served in the United States military. A few months after he registered for the draft, a new opportunity arose, an opportunity to participate in the liberation of his homeland. By the early part of 1919, Walter was marching across defeated Germany, one of 23,000 American volunteers marching under the crimson and white banner of the Polish republic, marching to unify a partitioned nation.

Sorry to go all Paul Harvey on you, but next time, I'll give you The Rest of the Story....and I'll say nary a word about Bose radios or "ocular nutrition tablets" or the soft, cool comfort of Jerzees cotton tee-shirts.................Good Day!